A view of the Supreme Court of Canada from the Ottawa River

Canada’s Top Court

The Supreme Court makes significant contributions to Canada’s strong and secure democracy, founded on the rule of law. Created in 1875, the Court is open, impartial and independent. As the country’s final court of appeal, it has jurisdiction over disputes in every area of the law. It is the guardian of the Constitution and Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Working together, the nine judges decide Canada’s most important and complex legal questions. They hear and decide cases in both French and English. The Court is also bijural, which means it applies the law according to common law and civil law legal traditions.

Cases most often come to the Supreme Court of Canada from provincial and territorial appeal courts. Appeals may also originate at the Federal Court of Appeal and the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada. Most cases are presented as requests for a hearing called an application for leave to appeal. Supreme Court judges will only hear cases they consider to be of national importance. There are exceptions in some criminal cases for automatic appeals where, for instance, a judge of an appeal court has dissented on a point of law. Supreme Court judges also answer reference questions that arise when a government asks the Court for an advisory legal opinion. Reference cases often ask if a proposed or existing legislation is constitutional, for example whether the federal government has the right to legislate certain activities. The Supreme Court has answered a wide variety of reference questions over the years, on topics such as same-sex marriage, Senate reform and medical assistance in dying.

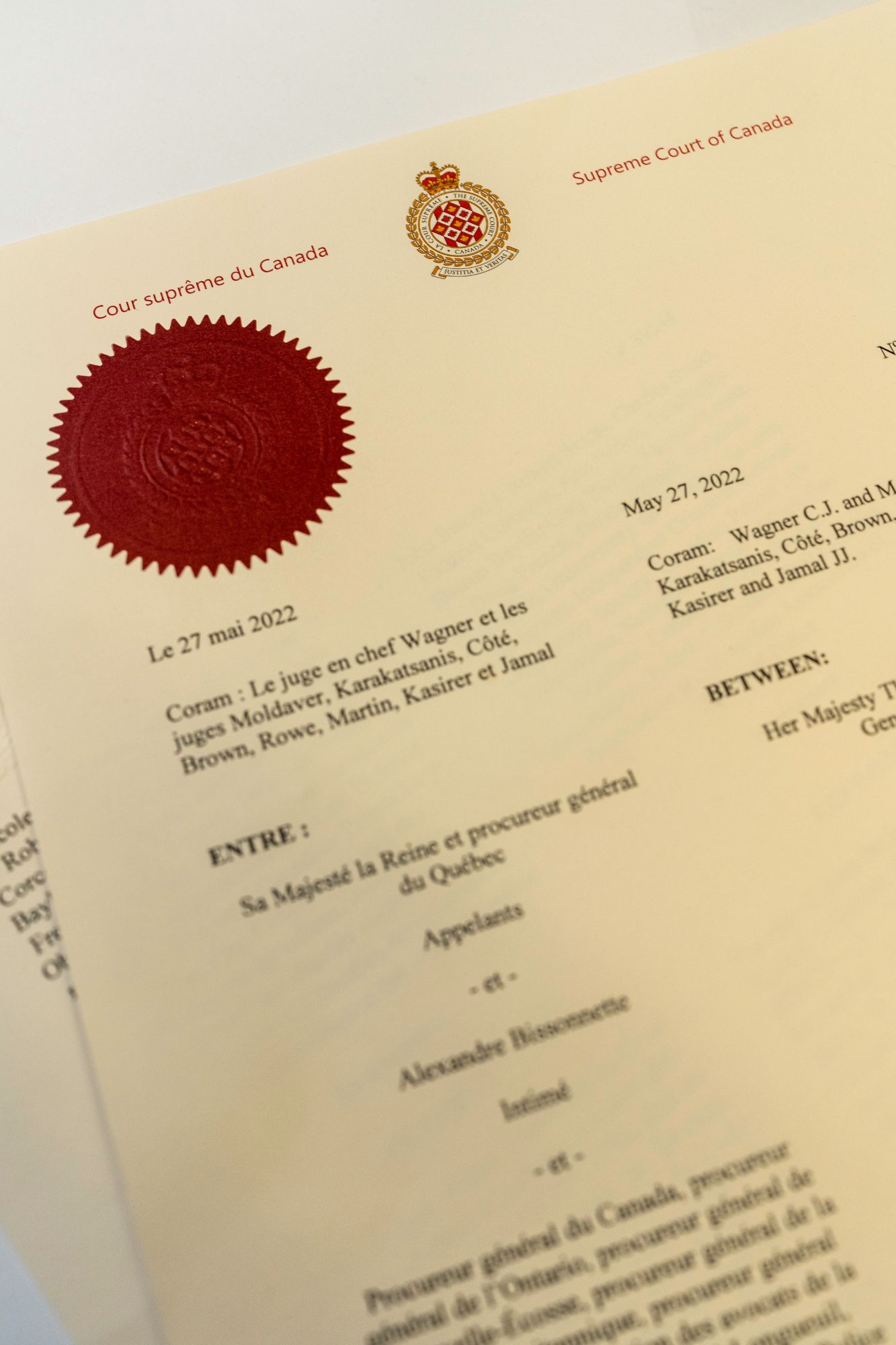

In 2022, the Court heard many criminal law appeals, as well as cases concerning everything from taxation to child custody. There are no trials or juries at the Supreme Court. No one testifies or introduces new evidence. Judges consider written and oral arguments from lawyers for the main parties, and ask them questions. They may also hear from interveners who often represent members of the public with a special interest on a legal issue.

The Supreme Court of Canada is an active and valued member of several international judicial organizations, and it regularly participates in professional exchanges with top courts around the world.

Current bench of the Supreme Court of Canada

Back row: Justices Jamal, Martin, Kasirer and O’Bonsawin

Front row: Justices Brown and Karakatsanis, Chief Justice Wagner, Justices Côté and Rowe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)